Benazir Bhutto’s Assassination And Pakistan’s Enduring Culture Of Political Violence

In Pakistan’s politics, the most consequential disagreements rarely end at negotiating tables. They end instead in courtrooms without verdicts, in prisons without closure, and at graves without accountability. The assassination of Benazir Bhutto, Pakistan’s first female prime minister and one of the most prominent democratic leaders in the Muslim world, was one such ending, not merely because it silenced a former prime minister, but because it exposed a political culture that continues to resolve disagreement without coexistence.

Benazir Bhutto was assassinated on 27 December 2007, in a gun-and-bomb attack after addressing an election rally in Rawalpindi. Just weeks earlier, she had survived a suicide bombing in Karachi that killed at least 123 people, one of the deadliest attacks in the country’s history. She was neither the first nor the last major political figure to be violently removed from Pakistan’s political stage.

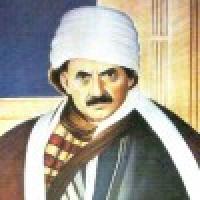

Pakistan’s first prime minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, was shot dead at a public meeting in Rawalpindi in 1951. Between these two deaths lie other forms of political elimination: the judicial execution of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the unexplained circumstances surrounding the death of leaders such as H.S. Suhrawardy, and the sudden demise of General Zia-ul-Haq in a plane crash that itself generated decades of suspicion. Together, they reflect a system that has struggled to resolve political conflict through institutions alone.

Political assassination in Pakistan has rarely been treated as a moral or systemic failure. Instead, it is routinely reduced to questions of security lapses or intelligence breakdowns. This framing misses the point. What these episodes expose is a deeper ethical collapse, a political order in which opponents are not seen as legitimate actors, but as threats to be neutralised. In mature political systems, even deeply polarising leaders are expected to lose power without losing life or liberty, returning to public life through elections, memoirs, or retirement rather than courts or graves. In Pakistan, politics has often operated on a more absolutist logic: that one side’s survival depends on the other’s removal.

© The Friday Times

Murat Sabuncu

Murat Sabuncu Tuğçe Tatari

Tuğçe Tatari Gürsel Göncü

Gürsel Göncü Kazım İlhan

Kazım İlhan Yılmaz Özdil

Yılmaz Özdil Arslan Bulut

Arslan Bulut Mustafa Mutlu

Mustafa Mutlu Saygı Öztürk

Saygı Öztürk Naim Babüroğlu

Naim Babüroğlu Ali Karahasanoğlu

Ali Karahasanoğlu Emin Çölaşan

Emin Çölaşan Rahmi Turan

Rahmi Turan Zülâl Kalkandelen

Zülâl Kalkandelen Murat Muratoğlu

Murat Muratoğlu Necati Doğru

Necati Doğru Korkusuz Kalem Osman Ferit

Korkusuz Kalem Osman Ferit Deniz Zeyrek

Deniz Zeyrek Soner Yalçın

Soner Yalçın Müyesser Yıldız

Müyesser Yıldız İsmet Özçelik

İsmet Özçelik Olaylar Ve Görüşler

Olaylar Ve Görüşler Mehmet Ali Güller

Mehmet Ali Güller Emre Kongar

Emre Kongar Memduh Bayraktaroğlu

Memduh Bayraktaroğlu Ahmet Takan

Ahmet Takan Aytunç Erkin

Aytunç Erkin Orhan Bursalı

Orhan Bursalı Dış Haberler Servisi

Dış Haberler Servisi Zafer Özcivan

Zafer Özcivan Uğur Kepekçi

Uğur Kepekçi Damla Doğan Tuncel

Damla Doğan Tuncel Özdemir İnce

Özdemir İnce Prof. Dr. Haydar Baş

Prof. Dr. Haydar Baş Risale-i Nurdan

Risale-i Nurdan Zeki Özdemir

Zeki Özdemir Doğu Perinçek

Doğu Perinçek Abdurrahman Dilipak

Abdurrahman Dilipak Can Ataklı

Can Ataklı Mehmet Y. Yılmaz

Mehmet Y. Yılmaz Barış Terkoğlu

Barış Terkoğlu Murat Ağırel

Murat Ağırel Ayşenur Arslan

Ayşenur Arslan